The 12th edition of Berry Go Round, the botanical blog carnival, is now online at Foothills Fancies. Lots of good reading to be had.

Filed under: Blog Carnivalia, Botany | Leave a comment »

The 12th edition of Berry Go Round, the botanical blog carnival, is now online at Foothills Fancies. Lots of good reading to be had.

Filed under: Blog Carnivalia, Botany | Leave a comment »

The characteristic peeling bark of Bursera simaruba. Copyright Kurt Stueber, licensed under the GFDL

Bursera simaruba has always been one of my favourite tree species. It’s a dry-season deciduous tree with compound leaves and a coppery peeling outer bark and a green (presumably photosynthetic) inner bark. It’s a conspicuous element of tropical dry forests in Trinidad and Tobago, Puerto Rico and parts of southern Florida (where they call it the ‘gumbo limbo’ tree). In all these places it’s the only representative of its genus. In my experience, Bursera was Bursera simaruba, so I was surprised when I came across a Bursera that was grown from seed collected in Costa Rica that was obviously not B. simaruba. Nonetheless, I still thought of Bursera as a relatively small genus. Then I came across some information on the genus in Mexico which turned my picture of Bursera completely on its head. There are 84 species of Bursera in Mexico – 80 of which are endemic – out of a total of approximately 100 species in the genus. So why are 80% of the species of Bursera – a genus which ranges from Florida to Argentina – restricted to Mexico?

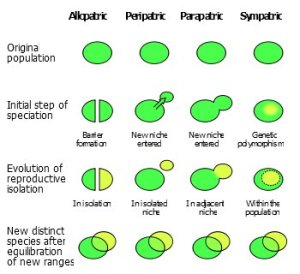

Species diversity patterns reflect several underlying processes – those that generate diversity, and those that maintain that diversity. When species are grouped into a genus, the assumption is that they are more closely related to one-another than are they to any species in a different genus. To get from that one ancestral species to its modern descendants, something must occur that allows the single ancestral lineage to split into several daughter lineages (a process known as speciation). This figure from the Wikipedia article on speciation summarises the different modes of speciation.

In order to generate the type of pattern seen in Bursera, you need one of two evolutionary processes to be active. Either Bursera originally diversified in Mexico, and a few species have spread beyond that ancestral range (giving rise to their own daughter species along the way) or something happened in Mexico that led to the diversification in a limited portion of the range of a widespread genus. In the former case, Mexican diversity should be old, and the splits between the Mexican species should lie deep in the ancestry of the genus. In the latter case, Mexican diversity is newer, and the splits between the Mexican species are likely to have been derived from more widespread species.

![]() In a paper published in PLoS ONE in October, Judith Becerra and Lawrence Venable of the University of Arizona looked at the case of Bursera in Mexico.1 Bursera is an old genus – molecular phylogenies based on ribosomal DNA suggest that modern species share a common ancestor about 66-74 million years ago, and fossil evidence suggests that the genus was once ranged over a much wider portion of North America.2 It turns out that most of the Mexican species are more recent. The number of lineages increased substantially within the last 30 million years3 and peaked between 10 and 17 million years ago (which coincides with the formation of the Western Sierra Madre and the Neovolcanic belt).1 Becerra suggested that the diversification of Bursera is likely to have coincided with the expansion of dry forests in central and southern Mexico.3 These dry forests were made possible by the uplift of the mountains which provided appropriate climatic conditions for the establishment of tropical dry forests by sheltering them from northern cold fronts.1

In a paper published in PLoS ONE in October, Judith Becerra and Lawrence Venable of the University of Arizona looked at the case of Bursera in Mexico.1 Bursera is an old genus – molecular phylogenies based on ribosomal DNA suggest that modern species share a common ancestor about 66-74 million years ago, and fossil evidence suggests that the genus was once ranged over a much wider portion of North America.2 It turns out that most of the Mexican species are more recent. The number of lineages increased substantially within the last 30 million years3 and peaked between 10 and 17 million years ago (which coincides with the formation of the Western Sierra Madre and the Neovolcanic belt).1 Becerra suggested that the diversification of Bursera is likely to have coincided with the expansion of dry forests in central and southern Mexico.3 These dry forests were made possible by the uplift of the mountains which provided appropriate climatic conditions for the establishment of tropical dry forests by sheltering them from northern cold fronts.1

In previous work, Becerra has built a detailed phylogeny of the Mexican species of Bursera. Using this phylogeny, she was able to show that the diversification of these species coincided with the formation of the Western Sierra Madre and the Neovolcanic belt. In the PLoS ONE article she and Venable used this phylogeny and the distribution of existing Bursera species to predict where the various species are likely to have originated. Despite the fact that it ranks third in Bursera species richness today, they found that the Southwest was actually the source of the largest number of species. The Balsas River basin, on the other hand, has the most species (and the largest number of endemic species), but was the site fo relatively few diversifications. Continued mountain-building led to an expansion of dry forest, into which new species wer able to spread. Other new species were able to invade the Mexican highlands, the Sonoran Desert, upland oak forests or subhumid tropical forests.

Becerra and Venable termed the diversity-generators “source” areas and the non-dry forest habitats as “diversity sinks”. Personally, this bothered me, as it felt like they were borrowing terminology from population ecology (where it applies to individuals within populations) and applying it to species in a way that is likely to bring unwanted baggage. Sink populations recruit fewer individuals than are required to replace losses to the population, and as such will go extinct if they don’t continue to receive immigrants from the source population. There’s nothing to indicate that Becerra and Venable are using ‘sinks’ to mean anything beyond the fact that these areas are occupied by species that evolved elsewhere. Using this borrowed terminology is likely to mislead readers who are more familiar with the concept of source-sink dynamics in population ecology.

Since certain areas have been superior generators of diversity, Becerra and Venable suggest that prioritising them for conservation should yield superior long-term outcomes. Protecting areas that can generate diversity should be more important than simply protecting areas that harbour greater diversity. They write:

The differences between diversity and diversification mean that this may be transitory in the long run, analogous to protecting species in zoos. While it might sound unusual to try to conserve diversity based on events happened in the past, there may be cases in which the aerographic patterns of diversification have occurred repeatedly for a long time, giving us some kind of assurance that it will continue happening in the same way for at least the near future. In the case of Bursera, diversification seems to have been higher in one area for a long time, starting 15 million years ago or perhaps even longer. If not greatly perturbed, there is no reason not to believe that these same patterns of diversification will continue. This approach could be especially useful if there are no other stronger criteria to decide where conservation efforts should be directed. If we had to choose between conserving one of two areas and everything is equal except their history of being sinks or sources of diversification, there would be no harm and perhaps much gain in choosing the source. The long-term maintenance of biodiversity require us preserve its sources, to the extent that these can be accurately determined [8].

[Emphasis added]

I’m not sure if I agree, or disagree. On one hand, there’s a lot of evidence that suggests that species assemblages are more transient than they were assumed to be in the past. The simple fact that an area supports a large assemblage of species may reflect chance as much as some special property of the site. So from that perspective, the areas that have generated diversity should be more important than the areas that harbour diversity. On the other hand, why should we assume that an area that generated a lot of diversity in the past will continue to do so in the future? The rate at which new species are being generated appears to have declined sharply in past 10 million years.3 If, as has been suggested, the generation of diversity was related to mountain-forming, is it reasonable to expect the process to continue? It’s difficult to say what it is that generates a species flock in one area and not in another.

The other big question I found myself with was what is the purpose of conservation? At what point will we be able to stop protecting species and environments? When will the threats recede, or will they recede at all? What will the world look like when the current human-driven extinction event has run its course?

This post is my contribution to PLoS ONE @ Two, a celebration of the second birthday of PLoS ONE.

Filed under: Ecology, Evolution, Tropical biology, Tropical dry forest | 2 Comments »

I discovered a new plant blog today, an apparently unnamed blog dedicated to “to edible, medicinal and otherwise useful tropical plant species and how they can be (and are being) integrated into diverse small and large scale agroforestry systems in both rural and urban environments”. For want of a better name, I’ll call it Anthrome, based on the first portion of its URL.

Filed under: Botany, Tropical biology | 2 Comments »

Edition #19 of the Oekologie blog carnival is up at Greg Laden’s blog. There’s lots of great stuff there, like Grrlscientist’s post on the evolution of poisonous birds, or a post from Sustainable Design Update on using coffee grounds as a source of biodiesel, or Greg Laden’s Congo Memoirs, or… Go. Read.

Filed under: Blog Carnivalia, Ecology | Leave a comment »

Ideas in Ecology and Evolution is a new open-access journal which “publishes only short forum-style articles that develop new ideas or that involve original commentaries on any topics within the broad domains of fundamental or applied ecology or evolution”. They also have an interesting review process:

Referees for Ideas in Ecology and Evolution are not anonymous; they are paid – not just for their reviewing services, but importantly, they are paid to forfeit their anonymity. In other words, in the event that the paper is published, payment of referees secures their consent to reveal their identities – directly within the published paper – as having refereed the paper. Referee identity is also revealed to authors of rejected papers. Referees must agree to these conditions in advance, before receiving the paper for review. This is done on-line, and the referee is paid upon receipt of the review.

The author pays for the review process and publication. It costs $400 to submit an article ($300 to pay two reviewers, $100 for the rest of the process) and an additional $300 upon acceptance. That’s the drawback of most open-access systems – that they require authors to incur substantial costs. Not that ‘closed-access‘ journals publish your articles for free…but it can still be a barrier for some authors. Granted, many of them are willing to waive their fees for authors who are unable to pay. I haven’t seen anything of the sort here, but that isn’t surprising in a journal this new.

Filed under: Ecology, Evolution, Open Access, Science communication | Leave a comment »

In a world of ever-increasing journal subscription prices, there’s a real need for an alternative model. Pricer journal subscriptions have led libraries to narrow the range of journals to which they subscribe. Much of the scientific literature is out of reach for institutions in poorer countries. Researchers working in these settings are less able to place their research in the context of modern research, which reduces their chance of having their work published. While some professional societies have tried to keep their subscription costs down, open-access publishing is becoming more attractive. Yesterday I blogged about OpenJ-Gate, a portal that provides access to a vast assortment of open-access journals. PLoS ONE is an “interactive open-access journal for the communication of all peer-reviewed scientific and medical research”. It combines open-access publishing with rapid publication. And then encourages readers to provide feedback. Bora Zvikovic, who blogs at A Blog Around the Clock is the PLoS ONE Community Manager.

This month, PLoS ONE will be celebrating its second birthday. In honour of that event, they are having a Synchroblogging Competition in collaboration with ResearchBlogging.org. In order to join in the fun (and maybe win some PLoS ONE swag) all you have to do is (a) register your blog with ResearchBlogging, and (b) on December 18, publish a blog post about one of the almsot 4,000 papers at PLoS ONE. Pretty simple? Of course, the post has to meet the standards of ResearcBlogging (read the paper and understand it, provide some serious commentary on the article). Bora has some more information here, and the official rules are here.

The biggest challenge, as I see it, is narrowing down what to write about. PLoS ONE has 335 ecology articles, and 115 plant biology artices (some of which, I presume, are not about Arabidopsis), so there’s lots of interesting stuff to sort through. There’s also lots of papers about minor fields like biochemistry, infectious disease, and other topics that somehow fall outside of the intersection of plant biology and ecology…

Filed under: Blogging, Open Access, Science communication | Leave a comment »

OpenJ-Gate, which bills itself as “the world’s biggest open access English language journals portal” , provides access to 4649 “academic, research and industry journals”, 2,528 of which are peer-reviewed. The site is run by Informatics India in support of the Open Access Initiative.

If you’re looking for open-access journals, it’s probably the place to start. You can browse journals by name and by subject, and you have access to each journal’s Table of Content. There are a couple negatives – while you can access the articles, they isn’t an obvious link to the journal itself. Sure, you can open an article and then work backward to the site’s URL, but the lack of easy links to the journal seems a tad unfriendly. In addition, the link to the journal’s archives is incomplete, at least in the case of the Journal of Tropical Forest Science. Overall though, it looks like a very valuable resource, especially for accessing less well-known journals.

Filed under: Open Access, Science communication | 1 Comment »

Deborah Howell, the Washington Post’s Ombudsman, took a look at science reporting. She opens by saying:

The job of science reporters is to take complicated subjects and translate them for readers who are not scientifically sophisticated. Critics say that the news media oversimplify and aren’t skeptical enough of financing by special interests.

Howell’s article, while it seems a little choppy, is well worth reading. Some of the points she makes are obvious – science reporting should be heavier on evidence and lighter on hype; that it’s important to determine whether the results are preliminary or published in a reputable journal/presented at a meeting*; that you need to look at who sponsored the research and other potential conflicts of interest. But beyond that, there are some things that I hadn’t thought about. David Brown, a Washington Post science reporter and physician, makes a good point when it comes to evaluating articles about science:

Brown recommends noticing how much space in an article is devoted to describing the evidence of the newsworthiness of the story and how much is devoted to someone telling you what to think about it. “If there isn’t enough information to give you, the reader, a fighting chance to decide for yourself whether something is important, then somebody isn’t doing his job, or hers.”

While this is useful for consumers of science reporting, it’s also something that anyone interested in science communication should keep in the forefront of their minds.

The thing that interested me most in the article was the discussion of what ends up on the front page. I have always taken for granted the fact that science stories are buried near the end of the first section. I never thought to ask why? I just figured that was the way it was, that it reflected some immutable law of the universe. And, of course, that front page stories selected themselves, not that there was editorial input into what ends up on Page 1. Howell writes

Don J. Melnick, professor of conservation biology at Columbia University, said that if a story “doesn’t sound newsworthy or front page-worthy, it will be buried or not printed at all. That tends to promote people hyping the research. They have to convince their editors to put it in the paper.”

That makes sense – everyone who wants their writing read engages in some amount of promotion or hype. But the next point is more enlightening

Nils Bruzelius, The Post’s science editor, said, “I thought the story and Page 1 play were justified because the potential impact was significant, even as I understand the criticisms. There’s an inevitable tension between the desire of reporters and editors to get good play for their stories and the need to avoid hype or overstatement, and we feel this very acutely in dealing with scientific or medical stories, because the advances, even those that prove to be part of something very big, usually come in incremental steps. I’ve long believed that science and medical stories enter this competition at some disadvantage. I certainly don’t have data on this but I suspect that most of the top editors who make the front-page decisions tend to be less drawn to these topics than the average reader because, with a few exceptions, they are a naturally self-selected group who got to where they are by dint of their interest and ability in covering such topics as politics, international relations, war and national security — not science.”

Fascinating.

*I think people put too much credence on “presented at a scientific meeting”. Sure, abstracts are screened, and your colleagues are there to critique your work. Maybe. There really isn’t enough information in most abstracts to judge their scientific merit properly. And while the big sessions and plenary speakers attract a large crowd, many sessions are small and many talks are presented to just a handful of people. So “presented at a scientific meeting” is a highly uneven measure of the quality of a discovery.

H/T DemFromCT at dKos

Filed under: Science communication | 1 Comment »

Festival of the Trees #30 is up at A Neotropical Savanna. There’s some great stuff there, including some great photography.

The Festival of the Trees blog carnival has acught my eye a couple times, but I have never clicked through and taken a good look at it. Much to my loss. It looks like the kind of thing that should really appeal to me – a mixture of tree biology and simple tree appreciation. On their “About” page they write

For the purposes of the Festival, we’re defining trees as any woody plants that regularly exceed three meters in height, though exceptions might be made to accommodate things like banana “trees” or bonsai. We are interested in trees in the concrete rather than in the abstract, so while stories about a particular forest would be welcome, newsy pieces about forest issues probably wouldn’t be. The emphasis should be on original content; we don’t want to link to pieces that are 90% or more recycled from other authors or artists.

The Festival of the Trees seeks:

- original photos or artwork featuring trees

- original essays, stories or poems about trees

- audio and video of trees

- news items about trees (especially the interesting and the off-beat)

- philosophical and religious perspectives on trees and forests

- scientific and conservation-minded perspectives on trees and forests

- kids’ drawings of trees

- dreams about trees

- trees’ dreams about us

- people who hug trees

- people who make things out of trees

- big trees

- small trees

- weird or unusual trees

- sexy trees

- tree houses

- animals that live in, pollinate, or otherwise depend on trees

- lichens, fungi or bacteria that parasitize or live in mutualistic relationships with trees

They also offer some pretty cool promotional badges…which I just couldn’t refuse. Hopefully that will remind me to send them a submission next time.

Filed under: Blog Carnivalia, Botany | Leave a comment »

The submission deadline for the Open Laboratory 2008 science bloggin anthology has passed, and Bora has posted a complete list of the submissions. Five hundred (or so) of the best science blog posts of the last year. As Laurent described it, “it’s like a Carnival”. It’s also a good place to go and update your RSS reader.

Filed under: Blogging, Science, Science communication | Leave a comment »